Dexlansoprazole

ticks all the

GORD boxes

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) – characterised by the retrograde flow of gastric contents into the oesophagus – is a chronic, progressive, and relapsing condition, affecting up to 33% of the global population.1

Indicators of GORD include oesophageal syndrome consisting of heartburn, regurgitation, and reflux chest pain syndrome, or non-cardiac chest pain, and possibly, extra‑oesophageal syndrome. Oesophageal exposure to gastric acid can be severe enough to cause an ulcer or peptic stricture, and even oesophageal adenocarcinoma.1

In addition, GORD may be a risk factor for other diseases including mental disorders, head and neck, respiratory as well as cardiovascular diseases.2

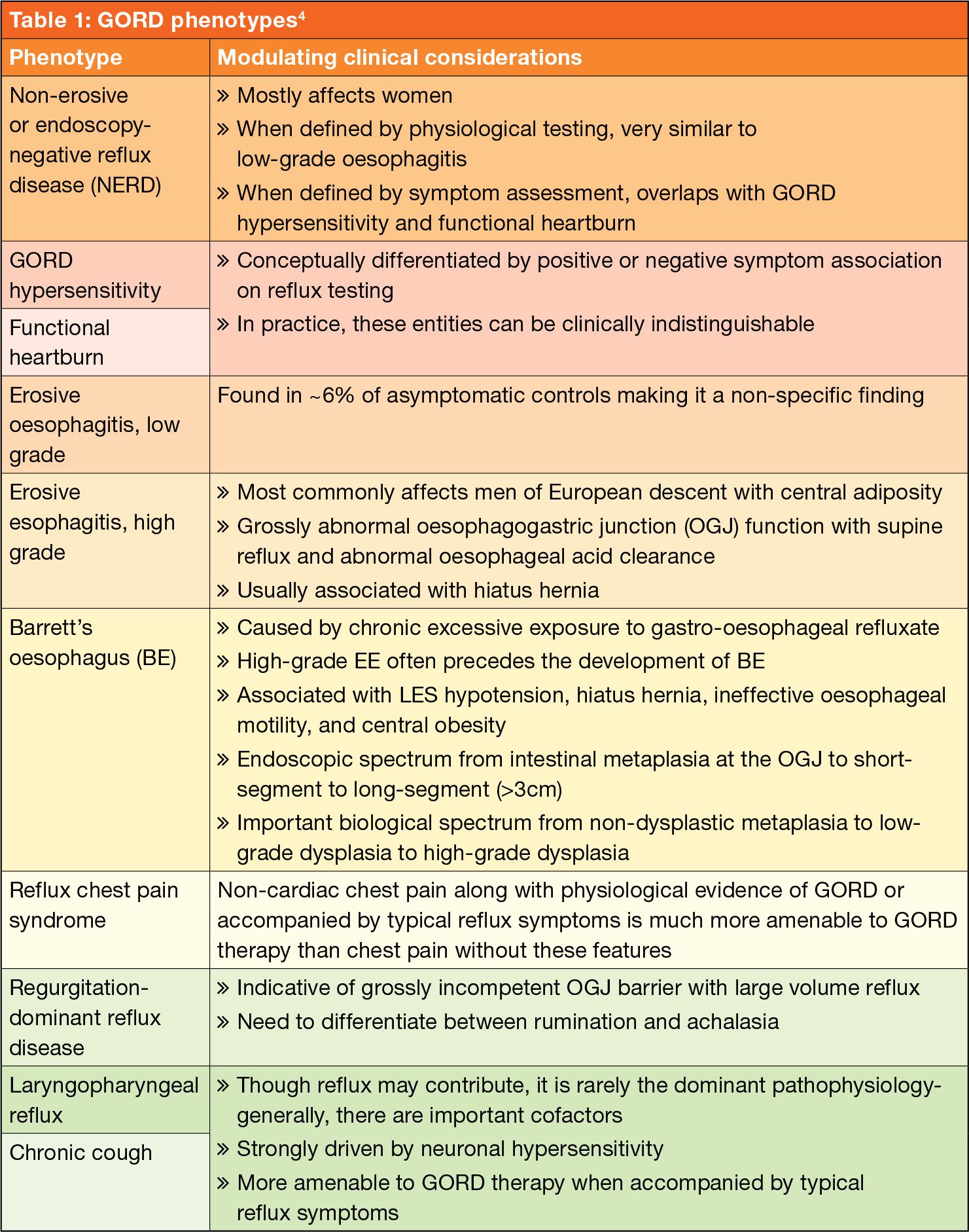

GORD phenotypes

Based on endoscopic and histopathologic appearance GORD can be classified into distinct phenotypes with unique predisposing cofactors and pathophysiology (see Table 1).3,4

Risk factors

Risk factors for GORD include:3

- Motor abnormalities (eg oesophageal dysmotility causing impaired oesophageal acid clearance, impairment in the tone of the lower oesophageal sphincter (LES), transient LES relaxation, and delayed gastric emptying)

- Anatomical factors (eg the presence of hiatal hernia or an increase in intra-abdominal pressure, as seen in patients living with obesity)

- Age ≥50-years

- Low socioeconomic status

- Tobacco use

- Consumption of excess alcohol

- Connective tissue disorders

- Pregnancy

- Postprandial supination

- Pharmacotherapy (eg use of anticholinergic drugs, benzodiazepines, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or aspirin use, nitro-glycerine, albuterol, calcium channel blockers, antidepressants, and glucagon).

How is GORD diagnosed?

According to the 2023 American Gastroenterology Association (AGA) expert review, there is no single diagnostic tool that can conclusively identify gastro-oesophageal reflux as the cause of extra-oesophageal symptoms. Determination of the contribution of gastro-oesophageal to extra-oesophageal symptoms should be based on the global clinical impression derived from patients’ symptoms, response to gastro-oesophageal therapy, and results of endoscopy and reflux testing.5

Initial testing to evaluate for reflux should be tailored to patients’ clinical presentation and can include upper endoscopy and ambulatory reflux monitoring studies of acid-suppressive therapy.5

Results from diagnostic testing (eg bronchoscopy, thoracic imaging, laryngoscopy, etc) from non-gastrointestinal (GI) disciplines should be taken into consideration when gastro-oesophageal reflux is considered as a cause for extra-oesophageal symptoms.5

Testing can be considered for those with an established objective diagnosis of GORD who do not respond to high doses of acid suppression. Testing can include pH-impedance monitoring while on acid suppression to evaluate the role of ongoing acid or non-acid reflux.5

Consideration should be given toward diagnostic testing for reflux before initiation of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy in patients with potential extra-oesophageal manifestations of GORD, but without typical GORD symptoms. Initial single-dose PPI trial, titrating up to twice daily, in those with typical GORD symptoms is reasonable.5

Symptom improvement of gastro-oesophageal reflux manifestations while on PPI therapy may result from mechanisms of action other than acid suppression and should not be regarded as confirmation for GORD.5

PPIs are the mainstay of pharmacotherapy for GORD

The AGA states that acid suppression with PPIs is the mainstay of pharmacologic therapy for GORD. Numerous randomised controlled studies have shown the effectiveness of these PPIs for healing of EE and controlling of typical symptoms of GORD such as heartburn and regurgitation.5

The AGA recommends PPI therapy (up to twice daily dosing for 8-12 weeks in empiric treatment) to address extra-oesophageal symptoms should be considered in patients with concomitant extra-oesophageal and oesophageal reflux symptoms, or in those with pathologic reflux documented through objective testing. In patients with extra-oesophageal symptoms alone, there is no clear evidence for empiric PPI therapy.5

Dexlansoprazole modified release (MR), launched in South Africa in 2022, is a new-generation PPI. In South Africa, dexlansoprazole is indicated for the treatment of erosive reflux oesophagitis, as well as for heartburn relief. Dexlansoprazole is also approved as maintenance therapy for up to six months in adults and for short-term treatment of heartburn and acid regurgitation associated with symptoms of NERD in adolescents.6,7

Due to its unique dual-release formulation, dexlansoprazole MR ensures the longest period of drug retention in circulation and the most powerful inhibitory effect on the proton pump of all available PPIs.6

Obesity is a risk factor for GORD and is significantly associated with reflux symptoms

The active ingredient of dexlansoprazole is released in two phases at different pH values and with a time interval. Thus, dexlansoprazole achieves two peak concentrations in the blood, and the total serum concentration is three times higher than that of the left-handed enantiomer.6

Furthermore, dexlansoprazole has a lower elimination rate than S-lansoprazole and persists longer in the serum. It inhibits acid secretion for a longer period, and its area under the curve values are three to five times higher than those determined for the racemic mixture or the left-handed isomer.6

Two distinct sets of enteric-coated granules are released from the capsule at different pH values. The first, representing 25% of the drug dose, is released at the pH level of 5.5 in the proximal duodenum. The second (75%) is released in the distal small intestine, where the pH is 6.75.6

This dual-release mechanism makes it possible to achieve two peak serum concentrations of the drug: one within one to two hours and the other within four to five hours after administration.6

Another unique feature of dexlansoprazole is that it can be taken with or without a meal, which improves adherence to treatment. According to Skrzydło-Radomańska and Radwan, only about 40% of patients take PPIs in line with recommendations, which results in weaker inhibition of acid secretion and represents one of the causes of therapeutic failure.6

Efficacy of dexlansoprazole

The efficacy of dexlansoprazole has been shown in numerous studies. Below as some of the highlights from these studies:8,15

- Heartburn was eliminated within four weeks in 50% of the patients receiving dexlansoprazole at a dose of 60mg, in 55% of the patients treated with the 30mg dose, compared to 19% of patients in the placebo group.8

- Dexlansoprazole 60mg and esomeprazole 40mg showed similar efficacy in the elimination of symptoms and healing of erosions. However, dexlansoprazole outperformed esomeprazole in alleviating symptoms in NERD patients.9

- Dexlansoprazole has been shown to improve nocturnal heartburn and sleep disorders. In a four week in patients (n=947) diagnosed with NERD, participants reported that dexlansoprazole 30mg provided a statistically significant higher percentage of days without heartburn for 24 hours and heartburn-free nights (54.9% and 80.8%, respectively) compared to placebo (18.5% and 51.7%, respectively).10

- In another study involving patients (n=305) with nocturnal heartburn and GORD-related sleep disorders, participants also reported a significant higher percentage of heartburn-free nights (73.1%) compared to placebo (35.7%), and the proportions of patients without sleep disorders after the therapy were 69.7% vs 47.9%.11

- EE healing was investigated in two eight-week studies involving patients (n=4092) with endoscopically confirmed EE. At the end of the study period, treatment with dexlansoprazole 60mg resulted in healed lesions in 92.3%-93.1% of the patients compared to 86.1%-91.5% of patients receiving 30mg of lansoprazole.12

- In a subgroup analysis of patients with moderate or severe EE, the percentages were: 88.9% of the patients cured with dexlansoprazole and 74.5% cured with lansoprazole.12

- Reflux EE is associated with a high risk of recurrence. The disease recurs in ~90% of cases during six- to 12-months. In patients with grade disease, reducing the dose of a PPI is sufficient for causing a recurrence in up to 41% of cases over a six-month period.13

- A study, which included patients (n=445) who successfully completed treatment for EE, compared the maintenance of the therapeutic effect and the alleviation of symptoms of dexlansoprazole (30mg and 60mg), compared to placebo, for a period of six months. The maintenance of healing rates in reflux EE achieved with dexlansoprazole at both doses were 74.9% and 82.5% respectively, compared to 27.2% for placebo.14

- A subgroup analysis of patients with severe EE both showed that the maintenance of heartburn relief over 24 hours was 96.1% and 90.9% for dexlansoprazole 30mg and 60mg respectively, compared to 28.6% for placebo. In both groups, the median percentage of heartburn-free nights was 98.9% and 96.2%, respectively, vs 71.7%.14

- In another study involving patients (n=178) with symptomatic GORD, successfully treated with a PPI twice a day, showed heartburn continued to be well-controlled in 88% of patients after switching from twice daily to dexlansoprazole 30mg once daily.15

Alternative treatment options

Alternative treatment methods to manage symptoms of GORD include lifestyle modifications, alginate-containing antacids, external upper oesophageal sphincter compression device, cognitive behavioural therapy, or neuromodulators) may play a role in management of symptoms.5

In terms of lifestyle modification, the AGA recommends avoidance of reflexogenic foods (eg chocolates, coffee, alcohol) food avoidance for at least two to three hours before recumbency, positional changes during the sleep period, and weight loss if needed.5

Late-evening meals have been shown to contribute to reflux. Head of bed elevation, as well as left lateral decubitus position, have been shown to improve nocturnal oesophageal acid exposure.5

As mentioned, obesity is a risk factor for GORD and is significantly associated with reflux symptoms and erosive esophagitis in a meta-analysis, and weight loss is associated with a reduction in symptoms and oesophageal acid exposure.5

In terms of surgery, the AGA states that shared decision-making should be performed before referral for anti-reflux surgery for gastro-oesophageal reflux when the patient has clear, objectively defined evidence of GORD.5

The AGA cautions a lack of response to PPI therapy predicts a lack of response to anti-reflux surgery and should be incorporated into the decision process.5

References

1. Zhang T, Zhang B, Tian W, et al. Trends in gastroesophageal reflux disease research: A bibliometric and visualized study. Front Med, 29 September 2022. Sec. Gastroenterology. Volume 9 – 2022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.994534

2. Li N, Yang WL, Cai MH, et al. Burden of gastroesophageal reflux disease in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of disease study 2019. BMC Public Health 23, 582 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15272-z

3. Antunes C, Aleem A, Curtis SA. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. [Updated 2022 Jul 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441938/

4. Katzka DA, Pandolfino JE, Kahrilas PJ. Phenotypes of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: Where Rome, Lyon, and Montreal Meet. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2020 Apr;18(4):767-776. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.07.015. Epub 2019 Jul 15. PMID: 31319183; PMCID: PMC6960363.

5. Chen JW, Vela MF, Peterson KA, Carlson DA. AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Diagnosis and Management of Extraesophageal Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: Expert Review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2023 Jun;21(6):1414-1421.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.01.040. Epub 2023 Apr 14. PMID: 37061897.

6. Skrzydło-Radomańska B, Radwan P. Dexlansoprazole – a new-generation proton pump inhibitor. Prz Gastroenterol, 2015;10(4):191-6. doi: 10.5114/pg.2015.56109. Epub 2015 Dec 16. PMID: 26759624; PMCID: PMC4697039.

7. MobiMims. Dexilant. Available from: https://www.mobimims.co.za/Product/Index?id=6c493702-225b-4501-98c3-b71393aea734

8. Behm BW, Peura DA. Dexlansoprazole MR for the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;5:439-45.

9. Wu MS, Tan SC, Xiong T. Indirect comparison of randomised controlled trials: comparative efficacy of dexlansoprazole vs. esomeprasole in the treatment of gastro-esophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2013;38:190-201.

10. Fass R, Chey WD, Zakko SF, et al. Clinical trial: the effect of the proton pump inhibitor dexlansoprazole MR on daytime and nightime heartburn in patients with non-erosive reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2009;29:1261-72.

11. Fass R, Chey WD, Zakko SF, et al. The effect of the proton pump inhibitor dexlansoprazole MR on nighttime heartburn and sleep disturbances in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol, 2011;106:421-31.

12. Sharma P, Shaheen NJ, Perez MC, et al. Clinical trials: healing of erosive oesophagitis with dexlansoprazole MR, a proton pump inhibitor with a novel delayed-release formulation – results from two randomized controlled studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2009;29:731-41.

13. Kahrilas PJ, Shaheen NS, Vaezi MF. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology, 2008;135:1392-413.

14. Metz DC, Howden CW, Perez MC, et al. Clinical trials: dexlansoprazole MR a proton pump inhibitor with dual delayed-release technology effectively controls symptoms and prevents relapse in patients with healed erosive eophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2009;29:742-54.

15. Fass R, Inadomi J, Han G, et al. Maintenance of heartburn relief after step-down from twice-daily proton pump inhibitor to once-daily dexlansoprazole modified release. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2012;10:247-63.